Бонусная политика 🎁

Эй, дружище! Если решил заценить Eldorado Casino, готовься к настоящему казино-патти. Тут тебе не просто возможность поиграть, а целая система ништяков, которые подстегивают азарт! Во-первых, давай про бездепозитный подарок, ведь тебя ждет главная фишка для новичков. Он, как бы «на халяву», так что обойдемся без пополнений, позволяющих забрать первый лут. При первом внесении денег тебе добавят до 100% к сумме, далее – 50%. Однако учти, призы придется отыграть по вейджеру х40. Другими словами, предстоит немного покрутить барабаны!

Теперь про возврат денег. Возврат вообще кайф! Каждую неделю можешь вернуть часть своих потерь. Кешбэк — своеобразная страховка. Поэтому, если тебе не повезло, не переживай — часть бабла вернется к тебе! Чем активнее играешь, тем выше ранг. Больше активности — больше ништяков. Другими словами, позже сможешь лутать еще больше вкусняшек. Всё очень просто: играй, прокачивай аккаунт и получай максимум от клуба.

Не забывай, здесь твои личные данные под надежной охраной, поэтому можешь не волноваться. Eldorado заботится о своих пользователях, позволяя сосредоточиться на игровом процессе. Поэтому, вперед, за кушем и удачей!

| Тип бонуса | Мин. депозит | Процент от депозита | Отыгрыш (Wager) | Промокод |

| Бонус на 1-й деп. | 200 рублей |

| х37 | Отсутствует |

| Бонус на 2-й деп. | 300 рублей |

| х37 | Отсутствует |

| Бонус на 3-й деп. | 500 рублей |

| х37 | Отсутствует |

Приветственный подарок новичкам

Эльдорадо дарит новичкам настоящие сокровища! Приветственные подарки дают шанс пройти теорию, найти практический опыт с возможностью выиграть реальные деньги. Чтобы забрать подарки, нужно сделать взнос. Чем больше вкладываешь, тем щедрее будут дары.

Первый взнос даст фриспины, которые распределяются по дням, поэтому сможешь наслаждаться развлечениями на протяжении нескольких дней. Второй и третий взносы также порадуют новыми фриспинами и дополнительными денежными вознаграждениями. Приветственный подарок — отличная возможность освоиться, возможно, заработать неплохие куши!

Промоакции ✨

Среди промоакций клуб предлагает:

- подарок 99% в слоте Hook Up доступен клиентам, проявлявшим активность 60+ дней. Это возможность получить x555 за спин;

- Октоберфест — бездепозитные награды размером до 5 555 рублей. Нужно участвовать в акциях марафона, забирать максимальное количество наград;

- турнир Pragmatic Play — седьмой раунд легендарной серии Drops & Wins. Каждый день разыгрываются крутые подарки и крупные денежные награды. Также предложены ежедневные турниры с призами до 5 000€;

- розыгрыш 280 000€ — свежий раунд Non-Stop Drop от Playson. Достаточно крутить слоты для получения рандомных призов;

- Колесо Фортуны — 3 бесплатных спина ежедневно. Полученные подарки нужно использовать за сутки, иначе они сгорят;

- установка мобильного приложения, за что награда составляет 99FS в Hugo 2;

- бои для героев — турниры с 3 призовыми местами;

- установка телеграм-бота @ElBot дает 33FS сразу после запуска бота;

- подписка Viber/Telegram — выдача специальных наград;

- активность по выходным — 30FS на Hugo за развлечения по субботам и воскресеньям;

- пятничный кешбэк — размер зависит от суммы взносов, сделанных за неделю.

Также клуб выдает подарки именинникам. Для их получения достаточно написать сотрудникам технической службы поддержки. Подарок активен 10 дней от даты рождения.

О Eldorado💡

Эй, друг! Давай немного поболтаем об Эльдорадо, которое стало настоящим раем для любителей азарта. Заведение запустилось в 2017 году, сегодня платформа разгоняет кучу эмоций и адреналина среди посетителей. Игровая платформа имеет лицензию, подтверждающую его надежность. Оно получило разрешение от властей Кюрасао. Другими словами, можешь спокойно крутить барабаны.

Что касается стран, где можешь наслаждаться азартными тайтлами Эльдорадо, тут все довольно просто. Клуб работает в большинстве стран, однако учти нюансы. Поэтому, если собираешься заносить бабосы, обязательно уточни, доступен ли игровой ресурс твоему региону.

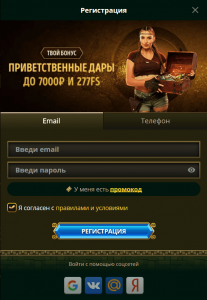

Процесс регистрации

Чтобы начать играть в Эльдорадо, нужно создать игровой профиль. Тут предложено 2 варианта создания аккаунта: стандартный и ускоренный. Если спешишь и хочешь быстрее попробовать все подарки, выбирай второй вариант. Однако обязательным условием является достижение возраста совершеннолетия. Вот как проходит стандартная процедура:

- Открываешь сайт.

- Нажимаешь кнопку “Регистрация”.

- Заполняешь все поля анкеты.

- Вводишь свои личные данные, не забывай про номер телефона, email.

- Соглашаешься с правилами и политикой клуба.

- Подтверждаешь регистрацию.

А если хочешь всё сделать быстрее, можно пройти ускоренный процесс через одну из соцсетей. Тогда создание личного кабинета будет выглядеть так:

- Открываешь платформу.

- Нажимаешь “Регистрация”.

- Выбираешь нужную социальную сеть из списка для авторизации:

- VK (Vkontakte)

- Mail.ru

- Яндекс

- Вводишь свои данные.

- Соглашаешься с правилами и политикой клуба.

- Проходишь активацию профиля по ссылке в письме.

После этого сможешь открыть игровой аккаунт и начинать вносить средства для игры. Однако для получения возможности вывести выигранные сокровища потребуется пройти процесс верификации.

Процесс верификации

Данная процедура — обязательный этап, позволяющий подтвердить свою личность и играть ставя деньги без проблем. Тебе придется показать документы, чтобы убедиться, что ты не какой-то мошенник! Процедура нужна для безопасности, поэтому не паникуй! Вот как пройти процедуру верификации игрового аккаунта:

- Открыть аккаунт: открой сайт Эльдорадо и посети созданный профиль.

- Открой специальный раздел: найди нужный пункт в настройках или личном кабинете.

- Подготовь документы: сделай фото или отсканируй документы, подтверждающие твою личность (например, паспорт или водительские права);

- Загрузи документы.

- Жди подтверждения: после загрузки документов дождись, пока служба поддержки проверит информацию. Подтверждение может занять немного времени;

- Получай доступ к развлечениям: как только твоя процедура пройдет, можешь спокойно играть и лутать!

Не забудь, что процедура нужна, чтобы мог без заморочек снимать кэш и не сталкиваться с проблемами.

Видеослоты 🎰

В Эльдорадо ассортимент видеослотов просто огромный! Помимо популярных слотов, найдешь другие интересные категории. Например, раздел “Crash” — тут найдешь азартные игры, где нужно вовремя вывести выигрыш, пока коэффициент растет. “Hold and Win” предлагает собирать символы и получать дополнительные призы, добавляющие азарта.

Если любишь классические развлечения, обязательно посети раздел “Настольные игры”. Здесь представлены такие хиты, как блэкджек, рулетка и баккара. А если хочешь поиграть с шансом получить дополнительные выигрыши, выбирай Тайтлы на бонусы, где можно ловить куши и разнообразные призы!

На платформе Эльдорадо представлено 65 популярных провайдеров, таких как Dynabit Gaming, 3 Oaks Gaming, NetEnt, Playson, Pragmatic Play, Endorphina, Yggdrasil. Большое количество провайдеров делает выбор по-настоящему впечатляющим! Также можешь быстро ориентироваться благодаря разделам:

- для тебя;

- провайдеры;

- популярное;

- новые;

- слоты;

- лайв-дилеры;

- crush;

- все;

- Hold and Win;

- настольные.

Каждый найдет что-то по своему вкусу!

| Автомат | Разработчик | RTP | Волатильность |

| Rise of Pyramids | Pragmatic Play | 95,5% | Средняя |

| Burning Wins x2 | Playson | 95,9% | Средняя |

| Myths of Bastet | OnlyPlay | 95,7% | Средняя |

| Book of Ra | Greentube | 92% | Высокая |

| Fire Joker | Play’N Go | 94,2% | Средняя |

| The Wish Master | NetEnt | 96,6% | Высокая |

| Crazy Monkey | Igrosoft | 96% | Средняя |

| Resident | Igrosoft | 95% | Средняя |

| Divine Fortune | NetEnt | 96,5% | Высокая |

Демо режим

Демо режим — твоя возможность поиграть без риска потерять деньги. Он идеально подходит для новичков, которые хотят освоить механики или просто развлечься без вложений. Главное отличие от реальной, что ты не ставишь деньги, а играешь используя условные фишки. Плюс, можешь протестировать разные видеослоты или настольные развлечения, прежде чем решишься сделать взнос. Демо режим — отличный способ подобрать подходящие азартные развлечения!

Игра на реальные ставки

Игра на реальные ставки — когда ставишь настоящие деньги и участвуешь в азартных развлечениях с шансом получить реальный выигрыш. Реальные ставки дают отличный способ развлечься и получить шанс одержать крутые заносы. Здесь рискуешь деньгами, поэтому важно быть осторожным. Плюс, когда выигрываешь, можешь выводить выигрыши и наслаждаться реальными призами! Если готов к азарту и ищешь адреналин, режим реальных ставок — подходящий выбор!

Игры с live-дилерами 🃏

Эльдорадо предлагает крутой раздел “Live Dealers”, где сможешь почувствовать настоящую атмосферу, играя за одним из 14 столов с живыми дилерами. Здесь представлены рулетка, блэкджек, покер, баккара и другие развлечения, которые проводят реальные ведущие. Режим с лайв-дилерами добавляет больше эмоций и интерактива, ведь играешь с настоящими людьми, а не просто с машиной.

Состязания 🤝

Эльдорадо предлагает испытать силы запустив турниры. Открой специальный раздел Турниры, который находится слева. Как только откроешь, перед тобой появится список актуальных предложений с подробной информацией. Тут увидишь срок действия турниров, размеры призов и имена победителей. Чтобы участвовать, нужно знать минимальную ставку, которая тоже указана. Турниры — отличный шанс прокачать навыки и побороться за крутую награду с другими азартными игроками!

Промокоды

Эльдорадо предлагает использовать промокоды, позволяющие получать дополнительные вознаграждения и предложения! Чтобы ввести код, просто выбери вкладку “Ввести промокод”. После того как введешь код, остается только нажать кнопку “Получить”. Это быстро, просто, а вознаграждения могут значительно улучшить игровой опыт! Поэтому не упусти возможность найти полезное для азартных приключений!

Внесение денег💸

В качестве валюты игровая платформа предлагает использовать рубли. Для проведения финансовых операций нужно нажать синюю кнопку “Касса” в верхней части экрана. Далее следует:

- Выбрать вкладку “Пополнить счет”.

- Выбрать платежную систему.

- Выбрать сумму.

- Нажать “Пополнить”.

Комиссия для взносов составляет 0%.

| Платежная система | Минимальная сумма | Максимальная сумма | Комиссия | Скорость поступления средств |

| FK Wallet | 100 рублей | 150 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

| Piastrix | 100 рублей | 300 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

| SkyPay | 1 000 рублей | 100 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

| Мир | 1 000 рублей | 100 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

| Visa | 1 000 рублей | 100 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

| Криптокошельки | 500 рублей | 500 000 рублей | 0% | Мгновенно |

Получение выигрышей 💳

Для вывода полученных выигрышей нужно нажать синюю кнопку “Касса” в верхней части экрана. Далее следует:

- Выбрать вкладку “Получить выигрыш”.

- Выбрать платежную систему.

- Указать сумму.

- Нажать “Вывести”.

Запросы получения выигрышей обрабатываются в течение 48 часов. Также, обязательным условием является пройденное подтверждение личности.

| Платежная система | Минимальная сумма | Максимальная сумма | Комиссия | Скорость вывода средств |

| FK Wallet | 100 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

| Piastrix | 100 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

| SkyPay | 3 000 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

| Мир | 3 000 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

| Visa | 100 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

| Криптокошельки | 100 рублей | — | 0% | до 24 часов |

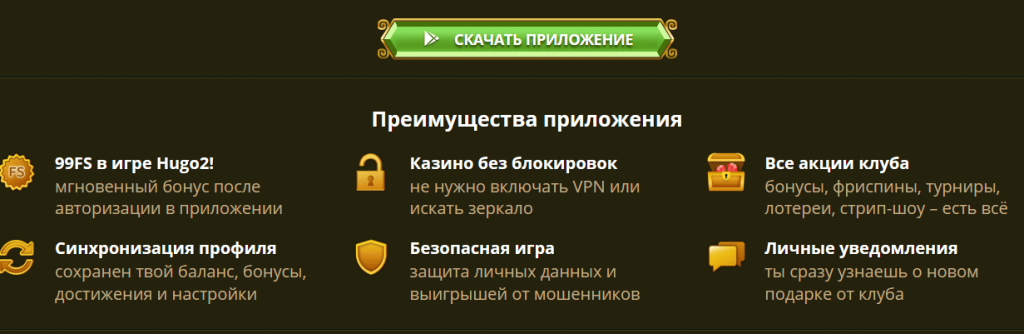

Мобильный клуб 📳

Мобильная версия Эльдорадо — отличный способ наслаждаться азартом вне дома! Здесь предложено много преимуществ, включая мгновенный подарок после авторизации и возможность залутать 99 фриспинов в Hugo 2. Можешь забыть о блокировках, ведь не нужно включать VPN или искать зеркала — все доступно в одном приложении.

Хотя здесь попадаются некоторые ограничения по сравнению с десктопной, все равно найдешь все промоакции клуба: награды, фриспины, турниры, лотереи и даже стрип-шоу! Профиль синхронизируется, поэтому баланс, награды и достижения сохранятся. Безопасность тоже высока: личные данные и твои выигрыши защищены от мошенников. Благодаря личным уведомлениям всегда будешь в курсе новых подарков от клуба!

Как скачать на Android

Чтобы загрузить приложение предложено 2 варианта действий. Первое — загрузить во вкладке “Скачать приложение”. Перед этим нужно:

- Включить настройки смартфона.

- Перейти во вкладку “Безопасность”.

- Перейти по ссылке на официальном сайте.

- Скачать мобильное приложение.

- Открыть вкладку загрузки на устройстве.

Остается установить загруженный файл. Второй вариант — опуститься вниз главной страницы официального портала и нажать кнопку “Скачай” на Android.

Как скачать на IOS

На iOS нет возможности загрузить приложение, однако не стоит расстраиваться — всегда можешь воспользоваться версией платформы через браузер. Это отличная альтернатива, позволяющая наслаждаться всеми азартными играми прямо с телефона, не теряя качество. Браузер поддерживает все основные функции, включая вознаграждения и промоакции, поэтому не пропустишь ни одного ништяка. Плюс, интерфейс адаптирован под маленький экран, делающий навигацию удобной и быстрой.

Техподдержка игровой платформы 🆘

Техподдержка для клиентов Эльдорадо всегда готова помочь и ответить на интересующие вопросы. Связаться можно несколькими удобными способами:

- телефон +79585815123 — быстрое решение проблем в разговоре с оператором

- электронная почта support@eldoclub.com — отправь вопрос, и ребята ответят тебе достаточно быстро;

- Телеграм https://t.me/eldorado_klub — удобно общаться используя мессенджер, получать оперативные ответы.

Служба работает круглосуточно.

Отзывы пользователей 🤙

Отзывы посетителей Эльдорадо положительные; многие гемблеры хвалят широкий выбор развлечений и щедрые подарки. Клиенты отмечают удобный интерфейс, который позволяет легко находить любимые слоты и попробовать турниры. Многие довольны качеством обслуживания и быстрым получением выигрышей. Однако некоторые пользователи выражают недовольство по поводу необходимости верификации и возможных задержек при обработке документов. Клуб получает много похвал за свои промоакции, однако есть моменты, которые требуют доработки.

Преимущества/недостатки клуба

Eldorado casino предлагает множество возможностей для азартных игроков. Плюсы:

- широкий ассортимент, включая слоты, настольные развлечения, лайв-дилеров;

- доступные награды, акции для новых и постоянных клиентов;

- наличие зеркала;

- удобный интерфейс, простое создание игрового аккаунта;

- возможность попробовать турниры, использовать промокоды.

Минусы:

- ограниченный доступ к некоторым тайтлам на смартфонах, планшетах;

- необходимость подтверждения личности для получения выигрышей.

Эти факторы делают Eldorado Casino привлекательным местом для азартных развлечений с небольшими нюансами!

FAQ ⁉️

- Как сыграть бесплатно в Эльдорадо?

Для этого нужно использовать демонстрационный режим.

- Как стать партнером Эльдорадо?

Для этого нужно воспользоваться партнерской программой, больше информации о которой представлено в специальном разделе в нижней части экрана.

- Как зайти на портал?

Для входа нужно использовать логин, пароль, указанные при создании учетной записи.

- Что такое кэшбэк в Эльдорадо?

Кешбэк — возврат части проигранных средств.

- Как забрать кешбек?

Кешбэк выдается еженедельно по пятницам.